- Advertisement -

Young Children and Communication | Complete Development Guide

Communication Development in Young Children | What Parents Need

- Advertisement -

Young Children and Communication

Understanding young children and communication development is one of the most crucial aspects of early parenting. From birth through age five, children accomplish the remarkable feat of learning to understand and use language—a complex system that forms the foundation for every relationship, academic achievement, and life success they’ll experience. Whether you’re a first-time parent wondering if your baby’s babbling is on track, a caregiver concerned about speech delays, or an educator seeking strategies to support language development in your classroom, this comprehensive guide provides everything you need to know about how young children and communication skills develop, what’s normal, and how to provide optimal support.

Research shows that the first three years of life represent a critical window for language acquisition, with children’s brains forming over one million neural connections every second. The quality and quantity of communication experiences during this period directly influence brain architecture, setting the stage for lifelong learning abilities. Yet despite its importance, many parents and caregivers feel uncertain about how to best support young children and communication development or when to seek professional help for concerns.

In this evidence-based guide, we’ll explore the fascinating journey of young children and communication, from prenatal hearing development through preschool conversations. You’ll discover the developmental stages children progress through, learn practical strategies you can implement today, understand how to identify potential concerns early, and gain confidence in nurturing one of your child’s most essential human capabilities.

Understanding Early Communication Development

What Is Communication in Early Childhood?

Communication in early childhood extends far beyond simply speaking words. It encompasses the entire spectrum of how children send and receive messages, including sounds, gestures, facial expressions, and eventually spoken language. Think of it as a complex dance where children learn to both express their needs and understand the world around them.

From birth, babies are hardwired for communication. They cry when hungry, smile when content, and make eye contact to connect with caregivers. These early interactions form the foundation for all future communication skills. Research shows that the quality and quantity of early communication experiences directly influence brain development, particularly in areas responsible for language processing and social cognition.

Young children’s communication abilities develop through a sophisticated interplay of biological readiness, environmental exposure, and social interaction. Their brains are remarkably plastic during these early years, making this period optimal for language acquisition. Every conversation, every book read aloud, and every song sung contributes to building neural pathways that support communication.

The Critical Period for Language Development

Scientists have identified what’s known as the “critical period” for language development, which extends from birth through approximately age seven, with the most sensitive window occurring before age three. During this time, children’s brains are exceptionally receptive to learning language patterns, sounds, and structures.

This doesn’t mean children can’t learn to communicate after this period, but the ease and naturalness of language acquisition is significantly enhanced during these early years. The brain’s plasticity during this time allows children to absorb multiple languages simultaneously, distinguish between subtle sound differences, and develop native-like pronunciation—abilities that become more challenging as we age.

Understanding this critical period helps parents and caregivers recognize the importance of rich language exposure during these formative years. Every interaction matters, and the communication foundation built during this time supports not just language skills but also reading, writing, and academic success later in life.

Stages of Communication Development in Young Children

Birth to 6 Months: The Foundation Stage

The journey of communication begins at birth. During the first six months, babies are busy learning the fundamentals of interaction. They communicate primarily through crying, which becomes increasingly differentiated—parents often learn to distinguish between a hunger cry, a tired cry, and a discomfort cry.

Around two months, babies begin cooing, producing those adorable vowel-like sounds that melt parents’ hearts. These coos represent the baby’s first experiments with their vocal apparatus. By three to four months, babies start responding to voices, turning toward sounds, and engaging in what researchers call “proto-conversations”—those delightful back-and-forth exchanges where baby coos, parent responds, baby coos again.

During this stage, babies also develop crucial non-verbal communication skills. They make eye contact, smile socially (around six weeks), and begin using facial expressions to convey emotions. These early interactions teach babies the fundamental rhythm and turn-taking nature of communication, setting the stage for more complex language development.

![Young Children and Communication Complete Development Guide]() 6 to 12 Months: Babbling and Pre-Language Skills

6 to 12 Months: Babbling and Pre-Language Skills

Between six and twelve months, communication takes a significant leap forward with the emergence of babbling. Initially, babies produce reduplicated babbling—repetitive syllable combinations like “bababa” or “dadada.” This evolves into variegated babbling, where babies mix different sounds together, creating patterns that sound increasingly like real speech.

This babbling isn’t random—it’s purposeful practice. Babies are experimenting with the sounds of their native language, and research shows that babbling patterns begin to reflect the specific sound patterns and intonation of the language they’re hearing. A baby growing up hearing Arabic will develop different babbling patterns than a baby hearing Mandarin.

During this period, babies also develop intentional communication. They begin pointing (typically around nine to twelve months), which represents a cognitive breakthrough—the understanding that they can direct another person’s attention to something of interest. They use gestures like waving, reaching, and nodding. These gestures often precede and predict spoken language development.

12 to 18 Months: First Words Emerge

The moment many parents eagerly anticipate arrives around the first birthday: the first recognizable word. Most children speak their first word between ten and fifteen months, though there’s considerable normal variation. These early words typically refer to important people (“mama,” “dada”), favorite objects (“ball,” “dog”), or social routines (“bye-bye”).

Early words often don’t sound exactly like adult versions—”ba” might mean “bottle,” or “ca” might mean “cat.” What matters is that the child uses the sound consistently to refer to the same thing. This consistency demonstrates true symbolic communication—understanding that specific sounds represent specific meanings.

During this stage, children’s receptive language (what they understand) far exceeds their expressive language (what they can say). A fifteen-month-old might only say five words but understand fifty or more. They can follow simple instructions like “give me the ball” or “come here,” demonstrating sophisticated comprehension even when production is limited.

18 to 24 Months: Vocabulary Explosion

Around eighteen months, many children experience what’s called the “vocabulary explosion” or “word spurt.” Their word learning accelerates dramatically, and they might add several new words daily. By age two, most children have a vocabulary of approximately fifty words, though some have many more.

This rapid vocabulary growth reflects important cognitive developments. Children begin to understand that everything has a name, leading to the charming (and sometimes exhausting) phase where they point at everything asking “What’s that?” They’re actively building their mental dictionary, categorizing the world around them.

During this period, children also begin combining words into two-word phrases—”more milk,” “daddy go,” “big dog.” These early combinations follow predictable patterns and demonstrate understanding of basic grammar concepts, even though they’re not yet producing complete sentences. This telegraphic speech, as it’s called, includes the most meaningful words while omitting function words like articles and prepositions.

2 to 3 Years: Combining Words and Simple Sentences

Between ages two and three, children’s language becomes increasingly sophisticated. They move from two-word combinations to three- and four-word sentences. Their vocabulary expands to several hundred words, and they begin using pronouns (“I,” “you,” “me”), prepositions (“in,” “on,” “under”), and asking questions.

The “terrible twos” reputation partly stems from a mismatch between children’s desires to communicate complex ideas and their still-developing language abilities. Frustration can result when children can’t express themselves as precisely as they’d like. However, this frustration also motivates continued language development.

By age three, most children can carry on simple conversations, tell simple stories (though not always coherently), and use language for various purposes—requesting, refusing, commenting, questioning, and expressing emotions. Their pronunciation improves, though many sounds may still be challenging. Strangers can usually understand about 75% of what a three-year-old says.

Types of Communication in Young Children

Verbal Communication

Verbal communication—using spoken words to convey meaning—is often what people think of first when discussing communication. For young children, developing verbal communication involves mastering multiple complex skills simultaneously: producing sounds correctly (articulation), combining sounds into words (phonology), learning word meanings (semantics), forming grammatically correct sentences (syntax), and using language appropriately in social contexts (pragmatics).

Each of these components develops along its own timeline but works together to create effective verbal communication. A child might have an excellent vocabulary but struggle with pronunciation, or speak clearly but have difficulty using language appropriately in social situations. Understanding these different components helps caregivers identify specific areas where a child might need support.

Young children’s verbal communication also reflects their thinking processes. When a three-year-old says “I goed to the park” instead of “I went to the park,” they’re not being careless—they’re applying grammatical rules consistently, which actually demonstrates sophisticated linguistic knowledge. These adorable errors gradually disappear as children learn the exceptions and irregularities of their language.

Non-Verbal Communication

Non-verbal communication remains critically important throughout early childhood, even as verbal skills develop. Young children are remarkably perceptive at reading non-verbal cues—facial expressions, tone of voice, body posture—often understanding the emotional content of communication before they fully grasp the words.

♦ Body Language and Gestures

Gestures serve multiple important functions in young children’s communication. They can compensate for limited vocabulary, emphasize verbal messages, or communicate when words aren’t available. Research shows that children who use more gestures tend to develop verbal language faster, suggesting that gestures support language development rather than hindering it.

Young children use various gesture types: deictic gestures (pointing to indicate objects or direct attention), iconic gestures (representing objects or actions, like flapping arms to indicate a bird), and conventional gestures (like nodding or waving, which have specific culturally agreed-upon meanings). These gestures become more sophisticated and integrated with speech as children develop.

Parents and caregivers naturally respond to children’s gestures, often providing the words that match the gesture—when a child points to a dog, an adult might say “Yes, that’s a dog!” This gesture-word pairing helps children make connections between symbols (words) and their referents (things in the world).

♦ Facial Expressions

Facial expressions are one of the earliest and most powerful forms of non-verbal communication. Even newborns respond preferentially to face-like patterns, and by a few months, babies can distinguish between happy, sad, and angry facial expressions. This ability to read faces is foundational for social communication and emotional development.

Young children learn to use facial expressions intentionally to communicate their emotions and desires. A toddler might exaggerate a sad face to elicit sympathy, or beam with pride when showing off an accomplishment. They’re also learning to monitor others’ facial expressions for social information—looking to a parent’s face when encountering something new to gauge whether it’s safe (social referencing).

The integration of facial expressions with verbal communication adds nuance and meaning to children’s messages. A child saying “I’m fine” with a frown communicates something quite different from the same words accompanied by a smile. Teaching children to notice this integration helps develop their overall communication competence and emotional intelligence.

Factors That Influence Communication Development

Environmental Factors

The environment in which a child grows up profoundly impacts communication development. Children raised in language-rich environments—where caregivers talk frequently, read books, sing songs, and engage in conversations—typically develop stronger language skills than children with limited language exposure.

Socioeconomic factors can influence communication development, though not deterministically. Research has documented what’s called the “30 million word gap,” referring to differences in the number of words children from different socioeconomic backgrounds hear by age three. However, quality matters as much as quantity. Responsive, engaged conversations support development more effectively than simply hearing lots of words in the background.

Physical environment matters too. Excessive background noise from televisions, radios, or crowded spaces can interfere with children’s ability to distinguish and learn language sounds. Quiet time for focused interaction supports optimal communication development. Access to books, toys that encourage imaginative play, and spaces for social interaction all contribute to creating communication-friendly environments.

Social Interaction and Relationships

Communication is fundamentally social, and young children learn language through interactions with others. The quality of these interactions matters tremendously. Responsive caregivers who follow children’s lead, expand on their utterances, and engage in genuine back-and-forth exchanges provide optimal support for communication development.

Attachment relationships influence communication development in multiple ways. Securely attached children tend to develop stronger communication skills, partly because they’re more likely to engage in sustained interactions with caregivers and partly because secure attachment supports the confidence needed to explore language. Children learn best from people they trust and feel connected to.

Peer interactions become increasingly important as children grow. While adult-child interactions provide language models and scaffolding, peer interactions offer opportunities to practice using language for social purposes—negotiating, cooperating, sharing ideas, and resolving conflicts. Both types of social interaction contribute uniquely to communication competence.

Cognitive Development

Communication and cognitive development are deeply intertwined. As children’s thinking becomes more complex, their communication reflects that complexity. The ability to form symbols, categorize experiences, understand cause and effect, and remember past events all support and are supported by language development.

Theory of mind—understanding that others have thoughts, feelings, and perspectives different from one’s own—is crucial for effective communication. Young children gradually develop this understanding, which allows them to adjust their communication based on their audience. A three-year-old might explain something differently to a baby versus an adult, demonstrating emerging theory of mind.

Executive functions like attention, working memory, and inhibitory control also impact communication development. Children need to maintain attention during conversations, remember what’s been said, plan their utterances, and inhibit irrelevant responses. These cognitive skills develop throughout early childhood and support increasingly sophisticated communication.

![Young Children and Communication Complete Development]() How to Support Your Child’s Communication Skills

How to Support Your Child’s Communication Skills

Talk, Read, and Sing Daily

The single most important thing you can do to support your child’s communication development is to talk with them—a lot. Narrate your daily activities, describe what you’re seeing, explain what you’re doing. This running commentary provides rich language input and helps children connect words with their meanings.

Reading together offers unique benefits for communication development. Books expose children to vocabulary and sentence structures they might not encounter in everyday conversation. The back-and-forth of shared reading—asking questions, making predictions, connecting stories to children’s experiences—builds multiple language skills simultaneously. Aim for at least 15-20 minutes of reading daily, starting from infancy.

Singing songs and reciting nursery rhymes support communication development in special ways. The rhythm and repetition help children remember language patterns, the rhyming builds phonological awareness (important for later reading), and the enjoyment strengthens positive associations with language. Don’t worry about your singing voice—your child thinks you sound wonderful!

Encourage Two-Way Conversations

While talking to your child is important, talking with your child is even more powerful. True conversations—with turn-taking, responsiveness, and mutual engagement—provide the richest language-learning opportunities. Even with very young children who can’t yet respond with words, you can create conversational exchanges by responding to their coos, babbles, and gestures as if they’re meaningful contributions.

Use open-ended questions that encourage more than yes/no answers. Instead of “Did you have fun today?” try “What did you do today?” or “Tell me about your favorite part.” When your child responds, show genuine interest, ask follow-up questions, and expand on what they’ve said. If a toddler says “doggy,” you might respond, “Yes, that’s a big brown dog! The dog is running fast. Where do you think the dog is going?”

Wait for responses. We often underestimate how much processing time young children need. After asking a question or making a comment, pause and give your child time to formulate a response. This wait time communicates that their contributions are valued and worth waiting for, and it reduces pressure that can inhibit communication.

Limit Screen Time

While technology isn’t inherently harmful, excessive screen time can interfere with communication development. Time spent watching screens is time not spent in interactive conversations, and children learn language best through responsive human interaction, not passive viewing.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends avoiding screen time (except video chatting) for children under 18 months, limiting to one hour of high-quality programming for children ages 2-5, and prioritizing co-viewing when screens are used. Co-viewing—watching together and talking about what you’re seeing—can transform passive screen time into an interactive learning experience.

When screen time is part of your child’s routine, choose high-quality, age-appropriate content designed with educational goals in mind. Look for programs that encourage interaction, use simple and clear language, and include repetition to support learning. Remember that screens should supplement, never replace, the real conversations that drive communication development.

Create a Language-Rich Environment

Beyond direct interactions, the overall environment shapes communication development. Fill your home with books at your child’s level, displayed where they can reach them. Include books in multiple languages if your family is multilingual. Rotate toys that encourage imaginative play and storytelling—dolls, action figures, play kitchen sets, puppets.

Label objects around your home to help children connect written and spoken words. Engage in play that naturally encourages communication—pretend play, building together, cooking together, playing simple games. These activities provide meaningful contexts for using language purposefully.

Minimize background noise when possible. Turn off the TV when no one’s watching, choose quiet times for focused conversations, and create spaces where your child can hear language clearly. This helps children distinguish speech sounds and attend to communication, supporting both language learning and listening skills.

Common Communication Challenges in Young Children

Speech Delays

Speech delays occur when a child’s speech development lags significantly behind age expectations. While there’s considerable normal variation in when children reach communication milestones, certain patterns warrant attention. A child with a speech delay might have a smaller vocabulary than expected, combine words later than typical, or be difficult to understand compared to same-age peers.

Speech delays can result from various causes: hearing problems, developmental conditions, limited language exposure, or sometimes no identifiable cause. The key is early identification and intervention. Research consistently shows that children who receive support early tend to have better long-term outcomes than those whose challenges go unaddressed.

If your child isn’t meeting expected milestones—no babbling by 9 months, no words by 16 months, no two-word combinations by age 2, speech that’s largely unintelligible by age 3—consult your pediatrician. They can conduct or refer you for a comprehensive evaluation to determine whether intervention is needed and what type would be most appropriate.

Language Disorders

Language disorders differ from speech delays in that they involve difficulty with the underlying aspects of language—understanding (receptive language) or using words, sentences, and conversation (expressive language). A child might pronounce words clearly but have trouble understanding questions or instructions, or might understand well but struggle to formulate sentences.

Specific language impairment (SLI), now often called developmental language disorder (DLD), affects approximately 7% of children. These children have persistent difficulties with language that aren’t explained by other conditions. Early signs include limited vocabulary, difficulty following directions, trouble answering questions, or persistent grammatical errors beyond the expected age.

Other conditions can impact language development, including autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and hearing loss. Comprehensive evaluation by a speech-language pathologist can identify the specific nature of difficulties and guide appropriate intervention strategies tailored to your child’s needs.

Selective Mutism

Selective mutism is an anxiety disorder where children speak comfortably in some situations but consistently fail to speak in others, despite having normal language abilities. Most commonly, children with selective mutism speak freely at home but remain silent at school or in other social situations.

This isn’t defiance or willful silence—it’s an anxiety response that children can’t simply overcome by trying harder. Children with selective mutism want to speak but feel physically unable to do so in anxiety-provoking situations. Without appropriate support, selective mutism can persist and interfere with academic and social development.

If your child consistently fails to speak in specific situations despite speaking normally in others, consult a mental health professional experienced with selective mutism. Treatment typically involves gradual exposure to speaking situations combined with anxiety management strategies, and early intervention significantly improves outcomes.

When to Seek Professional Help

Red Flags in Communication Development

While children develop at different rates, certain warning signs warrant professional evaluation. By 12 months, children should respond to their name, use gestures like waving or pointing, and vocalize with varied sounds. By 18 months, they should say at least a few words and follow simple instructions. By age 2, most children combine two words and have a vocabulary of at least 50 words.

Additional red flags include: loss of previously acquired language skills, frustration that interferes with daily functioning, frequent tantrums related to communication difficulties, difficulty following directions consistently, limited interest in social interaction, or persistent difficulty being understood by familiar adults. Regression—losing skills the child previously demonstrated—always warrants immediate evaluation.

Trust your instincts. Parents often notice subtle concerns before they’re obvious to others. If you’re worried about your child’s communication development, seeking evaluation costs little and provides valuable information. Even if assessment reveals no significant concerns, you’ll gain peace of mind and strategies for supporting continued development.

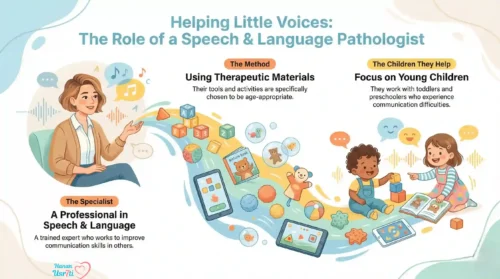

Types of Specialists Who Can Help

Several professionals specialize in evaluating and supporting children’s communication development. Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) assess all aspects of communication—articulation, language comprehension and expression, pragmatic skills, and feeding/swallowing. They provide therapy targeting specific difficulties and work with families to support communication at home.

Audiologists evaluate hearing, which is crucial since even mild hearing loss can impact communication development. If hearing issues are identified, audiologists can recommend and fit appropriate hearing aids or other devices. Early identification and treatment of hearing problems significantly improves communication outcomes.

Developmental pediatricians specialize in identifying and treating developmental concerns, including communication delays. They can provide comprehensive evaluation, diagnose underlying conditions, and coordinate care among various specialists. Psychologists or psychiatrists might be involved if communication difficulties relate to anxiety, selective mutism, or other mental health concerns.

The Role of Play in Communication Development

Interactive Play Activities

Play is children’s work, and it’s also their primary context for developing and practicing communication skills. Interactive play activities provide natural, meaningful opportunities to use language for various purposes—requesting, negotiating, pretending, planning, and problem-solving.

Simple games like peek-a-boo teach turn-taking and anticipation. Building blocks together encourages descriptive language and collaborative planning. Pretend play with dolls, action figures, or dress-up clothes creates rich scenarios for narrative language and role-playing conversations. These activities feel like fun to children while building crucial communication skills.

Arts and crafts activities naturally generate communication opportunities. Describing what you’re making, asking for materials, giving and following directions, and discussing the finished product all exercise different language skills. The key is being an engaged play partner—asking open-ended questions, expanding on your child’s ideas, and modeling slightly more complex language than they’re currently using.

Social Play and Peer Interaction

As children grow, peer play becomes increasingly important for communication development. Playing with other children requires negotiation, compromise, perspective-taking, and complex language use in ways that adult-child interactions don’t fully capture. Children learn to adjust their communication based on their playmate’s responses, developing flexibility and pragmatic skills.

Parallel play (playing alongside but not directly with other children) evolves into associative play (similar activities with some interaction) and eventually cooperative play (working together toward shared goals). Each stage supports different communication skills. Even conflicts during play—when handled constructively—teach children to use language for problem-solving and emotional regulation.

Facilitate peer play opportunities through playdates, parent-child classes, library story times, or preschool programs. Initially, children may need adult scaffolding to navigate peer interactions successfully, but gradually they develop the skills to manage play interactions independently, using increasingly sophisticated communication to coordinate, negotiate, and maintain friendships.

Technology and Young Children’s Communication

Benefits and Risks of Digital Media

Technology presents both opportunities and challenges for young children’s communication development. On the positive side, video calling allows children to connect with distant family members, maintaining relationships that support emotional and communication development. High-quality educational apps designed for young children can supplement learning, particularly for children who need extra practice with specific skills.

However, significant risks exist when screens replace human interaction. Passive screen time doesn’t provide the responsive, contingent interactions that drive language learning. Children learn communication skills from live, face-to-face interactions far more effectively than from even the highest-quality programming. Additionally, excessive screen time has been linked with attention problems, sleep disruption, and reduced time for active play—all factors that can impact development.

The touchscreen nature of tablets and smartphones can be particularly problematic for communication development. While these devices feel interactive because children can swipe and tap, they don’t provide true back-and-forth communication. Apps rarely respond contingently to children’s unique utterances the way a responsive caregiver would, limiting their effectiveness for language learning.

![Young Children and Communication]() Best Practices for Screen Use

Best Practices for Screen Use

If screens are part of your family’s life, implement practices that minimize risks and maximize benefits. Co-view content with your child, talking about what you’re watching and asking questions. This transforms passive viewing into an interactive experience. Choose programming specifically designed for young children, with simple storylines, clear language, and educational content.

Establish screen-free zones and times—no screens during meals, an hour before bedtime, or during family activities. These boundaries ensure screen time doesn’t displace crucial face-to-face interactions and activities that support communication development. Keep screens out of children’s bedrooms entirely, as bedroom screen access correlates with increased use and sleep disruption.

When choosing media, look for content that encourages interaction, uses repetition to support learning, and models prosocial behavior and conversations. Avoid fast-paced content with frequent cuts, which can impact attention development. Remember that screens are tools—they can support development when used thoughtfully and deliberately, but they should never replace the human interactions that are essential for communication growth.

Multilingual Communication in Young Children

Benefits of Bilingualism

Growing up bilingual offers tremendous advantages. Bilingual children develop enhanced executive function skills—the ability to focus attention, switch between tasks, and hold information in working memory. They show advantages in metalinguistic awareness (thinking about language itself) and perspective-taking abilities. Far from confusing children, bilingualism enhances cognitive flexibility.

Bilingual children connect with multiple cultural communities, access broader opportunities for education and employment, and develop appreciation for linguistic and cultural diversity. They can communicate with extended family members who may speak different languages and access literature, media, and ideas in multiple languages. These benefits extend throughout life, and research suggests bilingualism may even provide some protection against cognitive decline in aging.

Concerns that bilingualism delays language development are largely unfounded. While bilingual children may initially have somewhat smaller vocabularies in each individual language, their total vocabulary across both languages typically equals or exceeds monolingual peers. Any minor delays in reaching certain milestones are temporary and far outweighed by the long-term advantages of bilingualism.

Supporting Multiple Languages at Home

Families raising bilingual children can use various approaches successfully. The “one person, one language” approach, where each parent consistently speaks a different language to the child, works well for many families. Alternatively, families might use different languages in different contexts—one language at home, another in the community—or different languages at different times.

Consistency matters more than the specific approach. Children learn languages most effectively when they receive regular, sustained exposure and opportunities to use each language meaningfully. Aim for at least 30% of waking time exposed to each language, though more is better. Reading books, singing songs, and conversing in both languages all support development.

Don’t worry about children mixing languages (code-switching). This is a normal part of bilingual development, not a sign of confusion. Bilingual children actually demonstrate sophisticated understanding by code-switching appropriately—using vocabulary from whichever language offers the best word for their meaning. As they develop stronger skills in each language, mixing typically decreases, though it may persist as a natural feature of bilingual communication.

Conclusion

Young children’s communication development represents one of the most remarkable achievements of early childhood. From first cries to full conversations, children navigate an incredibly complex journey, mastering the intricate systems of sound, meaning, grammar, and social use that enable human connection. As parents, caregivers, and educators, we have the privilege and responsibility of supporting this crucial development.

The strategies outlined in this guide—talking frequently with children, reading together, encouraging play, limiting screen time, and creating language-rich environments—aren’t complicated or expensive, but they’re profoundly effective. Communication skills built during these early years form the foundation for literacy, academic success, relationships, and virtually every aspect of life.

Remember that every child develops at their own pace, and variation is normal. However, trust your instincts when something concerns you, and don’t hesitate to seek professional guidance. Early identification and intervention for communication difficulties can dramatically improve outcomes. Above all, enjoy this incredible journey with your child. Those first words, those hilarious mispronunciations, those lengthy toddler monologues—these are precious moments in your child’s emerging ability to share themselves with the world.

FAQs

1. At what age should my child say their first word?

Most children speak their first recognizable word between 10 and 15 months, though there’s considerable normal variation. Some children say their first word as early as 8-9 months, while others don’t speak until closer to 18 months. What matters more than the exact timing is overall developmental trajectory. If your child isn’t saying any words by 16 months, shows no interest in communicating, or has lost previously acquired language, consult your pediatrician for evaluation.

2. Is it normal for my toddler to understand much more than they can say?

Absolutely! Receptive language (understanding) consistently develops ahead of expressive language (speaking) in young children. A typical 15-month-old might only say 5-10 words but understand 50 or more. This gap is completely normal and actually demonstrates healthy language development. Children are building their internal language system and will express more as their motor skills for speech production catch up to their comprehension.

3. Should I correct my child’s grammar mistakes?

Rather than directly correcting errors, use a technique called “recasting”—repeat what your child said using correct grammar. If your toddler says “I goed to park,” you might respond, “Yes, you went to the park! What did you do at the park?” This provides the correct model without making children feel criticized or self-conscious about their speech. Direct corrections can reduce children’s willingness to communicate and don’t teach grammar as effectively as natural modeling does.

4. How much talking should I do with my young child?

As much as possible! Research shows that children who hear more words develop stronger language skills. Aim for continuous conversation throughout daily activities—narrate what you’re doing, describe what you see, ask questions, and respond to your child’s communications. Quality matters too—responsive, back-and-forth conversations support development better than just background talk. Even 15 minutes of focused, engaged conversation daily can significantly impact development.

5. When should I be concerned about my child’s communication development?

Key milestones to watch for include: responding to name by 12 months, using gestures like pointing and waving by 12 months, saying a few words by 18 months, combining two words by 24 months, and being understood by strangers at least 50% of the time by age 3. Additional concerns include: loss of previously acquired skills, extreme frustration related to communication, limited interest in social interaction, or persistent difficulty following simple directions. When in doubt, seek evaluation—early intervention, if needed, produces the best outcomes.

6 to 12 Months: Babbling and Pre-Language Skills

6 to 12 Months: Babbling and Pre-Language Skills How to Support Your Child’s Communication Skills

How to Support Your Child’s Communication Skills Best Practices for Screen Use

Best Practices for Screen Use