- Advertisement -

Children Reading and Writing | Complete Development Guide 2026

How to Improve Children Reading and Writing Skills

- Advertisement -

Children’s Reading and Writing Development

In today’s fast-paced digital age, where screens compete for attention and information floods in from every direction, helping children develop strong literacy skills has become both more challenging and more essential than ever before. Whether you’re a parent watching your toddler scribble their first letters or an educator guiding a classroom of emerging readers, understanding the journey of literacy development can transform how you support the children in your life.

Children reading and writing skills form the cornerstone of academic success and lifelong learning. If you’re searching for effective strategies to support children reading and writing development, you’ve come to the right place. This comprehensive guide reveals evidence-based techniques that parents and educators use to transform struggling learners into confident, capable readers and writers.

Whether you’re wondering when children reading and writing abilities should emerge, how to identify developmental delays, or what activities genuinely improve literacy skills, this article provides answers backed by educational research and practical classroom experience. From understanding the critical stages of children reading and writing development to implementing daily strategies that actually work, you’ll discover everything needed to support young learners on their literacy journey.

In this guide, you’ll learn:

- The five essential stages of children reading and writing development

- Proven techniques to encourage reluctant readers and writers

- How to identify and address common literacy challenges

- Expert-recommended resources and tools for home and classroom

- Age-appropriate milestones and assessment strategies

Children reading and writing proficiency doesn’t happen by accident—it requires intentional support, quality instruction, and consistent practice. Let’s explore how you can make a meaningful difference in a child’s literacy development, starting today.

Why Reading and Writing Skills Matter for Children

Cognitive Benefits of Early Literacy

Reading and writing aren’t just subjects children study in school—they’re fundamental cognitive processes that literally reshape how young brains develop and function. When children engage with written language, they’re building neural pathways that support critical thinking, problem-solving, and abstract reasoning.

Key cognitive advantages include:

- Enhanced vocabulary acquisition and language processing

- Improved memory retention and recall abilities

- Stronger analytical and critical thinking skills

- Better concentration and attention span

- Increased imagination and creative thinking capabilities

Research from neuroscience shows that reading activates multiple brain regions simultaneously, creating a complex neural network that supports learning across all subjects. Children who develop strong literacy skills early often demonstrate advantages in mathematics, science, and even social studies because reading comprehension is the gateway to accessing information in every domain.

Think of literacy skills as the operating system of learning—without them functioning properly, every other educational application struggles to run smoothly.

Social and Emotional Development Through Literacy

Beyond the obvious academic benefits, reading and writing play a profound role in children’s emotional intelligence and social development. When children read stories, they step into other people’s shoes, experiencing different perspectives, cultures, and emotional situations in a safe, imaginable space.

Social-emotional benefits include:

- Developing empathy by understanding characters’ feelings and motivations

- Building emotional vocabulary to express their own feelings

- Gaining confidence through mastery of new skills

- Creating connections with peers through shared reading experiences

- Processing complex emotions through journaling and creative writing

Writing, in particular, gives children a powerful tool for self-expression. Whether they’re composing a story about a brave knight or writing about their day in a journal, children learn to organize their thoughts, reflect on experiences, and communicate their inner world to others.

Academic Success and Future Opportunities

The statistics are compelling: children who read proficiently by third grade are significantly more likely to graduate high school and pursue higher education. This “third-grade reading milestone” has become a recognized predictor of long-term academic and career success.

| Reading Proficiency Level | High School Graduation Rate | College Attendance Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Below Basic | 58% | 23% |

| Basic | 75% | 42% |

| Proficient | 89% | 67% |

| Advanced | 95% | 84% |

Strong literacy skills open doors throughout life—from filling out job applications to understanding contracts, from enjoying literature to participating meaningfully in civic life. In our information-rich society, the ability to read critically and write clearly has become an essential life skill, not just an academic requirement.

Understanding the Stages of Reading Development in Children

Pre-Reading Stage (Ages 0-5)

Long before children can decode their first word, they’re building the foundational skills that make reading possible. This pre-reading stage is absolutely crucial, and it begins from infancy.

Essential pre-reading skills include:

- Print awareness» Understanding that text carries meaning and flows in a particular direction

- Phonological awareness» Recognizing and playing with sounds in language (rhyming, alliteration)

- Letter recognition» Identifying letter shapes and beginning to associate them with sounds

- Vocabulary development» Building a rich oral vocabulary through conversations and exposure

- Listening comprehension» Understanding stories read aloud

During this stage, children are like sponges, absorbing language patterns, building neural connections, and developing the cognitive architecture that reading will later build upon. The child who has been read to extensively, who has played word games, and who has seen adults modeling reading behavior enters formal reading instruction with tremendous advantages.

What this looks like in practice: A three-year-old might pretend to read by telling a story based on the pictures in a familiar book, pointing to words randomly but with purposeful gestures that mimic actual reading.

Beginning Reading Stage (Ages 5-7)

This is when the magic really starts to happen. Children begin connecting those abstract squiggles on the page to sounds and meanings. It’s a complex cognitive achievement that involves coordinating multiple skills simultaneously.

Key milestones of beginning readers:

- Mastering letter-sound correspondence (phonics)

- Blending sounds together to decode simple words

- Recognizing high-frequency sight words automatically

- Reading simple sentences with increasing fluency

- Beginning to use context clues and picture support

During this stage, reading often feels effortful for children. They’re working hard to decode each word, sometimes sounding them out letter by letter. Their oral reading might sound choppy or robotic as they focus intensely on the mechanics of decoding. This is completely normal and expected.

Educator insight: Think of beginning readers like people learning to drive. At first, they’re consciously thinking about every single action—checking mirrors, pressing pedals, turning the wheel. With practice, these actions become automatic, freeing up mental energy for navigation and responding to traffic.

Fluent Reading Stage (Ages 7-9)

As children practice and develop automaticity with decoding, something remarkable happens—reading transforms from laborious work to an increasingly automatic process. This frees up cognitive resources for the real goal: comprehension.

Characteristics of fluent readers:

- Reading with appropriate speed, accuracy, and expression

- Automatically recognizing most words without conscious decoding

- Self-correcting when reading doesn’t make sense

- Beginning to read silently with comprehension

- Engaging with increasingly complex texts and longer books

Fluency is the bridge between decoding and comprehension. When children no longer need to devote all their mental energy to figuring out what words say, they can focus on what those words mean. This is when reading often shifts from a school task to a potential source of enjoyment and information-seeking.

Advanced Reading Stage (Ages 9+)

Advanced readers have mastered the mechanical aspects of reading and now use reading as a tool for learning and pleasure. They can tackle complex texts with multiple perspectives, abstract concepts, and sophisticated vocabulary.

Advanced reading skills include:

- Reading to learn new information across subject areas

- Analyzing text structure and author’s purpose

- Making inferences and reading between the lines

- Critically evaluating information and sources

- Integrating information from multiple texts

- Adjusting reading strategies based on purpose and text type

At this stage, the focus shifts from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” Children should be exposed to diverse genres, challenging vocabulary, and texts that stretch their comprehension abilities while still providing appropriate support.

The Writing Development Journey

Pre-Writing Skills and Fine Motor Development

Before children can form letters on paper, they need to develop the fine motor control that makes writing physically possible. This development begins in infancy and progresses through early childhood.

Foundational pre-writing skills:

- Grasping and manipulating objects (building hand strength)

- Scribbling and making marks with crayons or markers

- Drawing basic shapes (circles, lines, crosses)

- Developing hand-eye coordination

- Building the tripod grasp for pencil holding

Parents and educators sometimes underestimate the importance of activities like playing with playdough, stringing beads, or using scissors—but these activities build the exact motor skills children need for writing. The three-year-old squeezing playdough is literally strengthening the hand muscles they’ll use to grip a pencil.

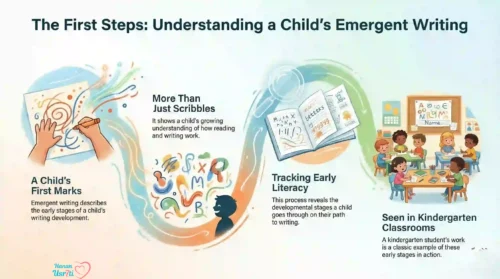

Emergent Writing Stage

Children’s first attempts at writing are precious documents that reveal their growing understanding of how written language works. Emergent writing includes everything from random scribbles to letter-like forms to actual letters used without conventional spelling.

Typical progression:

- Random scribbling: Making marks that don’t yet represent anything specific

- Controlled scribbling: Lines that follow the direction of writing in their language

- Letter-like forms: Shapes that resemble letters but aren’t quite accurate

- Random letters: Actual letters used without sound-symbol correspondence

- Invented spelling: Using letters to represent sounds they hear in words

When a four-year-old writes “ILVUBLU” for “I love you,” they’re demonstrating sophisticated phonological awareness and understanding of the alphabetic principle—that letters represent sounds. This should be celebrated, not corrected with red pen.

Transitional Writing Stage

As children progress through elementary school, their writing becomes increasingly conventional while their ideas become more complex. This transitional period involves learning the rules and patterns of standard English spelling and grammar while developing their voice and style.

Characteristics of transitional writers:

- Using conventional spelling for high-frequency words

- Applying phonetic spelling strategies for unfamiliar words

- Writing in complete sentences with appropriate punctuation

- Organizing ideas into simple paragraphs

- Beginning to revise and edit their work

- Experimenting with different writing genres

During this stage, children benefit from explicit instruction in spelling patterns, grammar rules, and writing structures while still being encouraged to take risks and express their ideas freely. The challenge is balancing skill development with creativity and voice.

Conventional Writing Mastery

As children move into upper elementary and middle school, their writing should demonstrate increasing sophistication in both mechanics and content. They’re now capable of producing well-organized, multi-paragraph compositions with clear purposes and audiences.

Advanced writing competencies:

- Producing organized, coherent multi-paragraph compositions

- Using varied sentence structures and transitions

- Applying advanced grammar and punctuation correctly

- Incorporating research and evidence into writing

- Revising for content, organization, and style

- Adapting writing for different purposes and audiences

- Developing a personal writing voice

Effective Strategies to Encourage Reading in Children

Creating a Reading-Rich Environment

Children learn to value what they see valued in their environment. If books are treasured, accessible, and integrated into daily life, children naturally gravitate toward them.

How to build a literacy-rich home or classroom:

- Create inviting reading spaces: Comfortable seating, good lighting, and attractive book displays make reading appealing

- Make books accessible: Keep books at children’s eye level and within easy reach

- Display varied genres and formats: Picture books, chapter books, magazines, comics, nonfiction, poetry

- Model reading: Let children see adults reading for pleasure and information

- Integrate print into daily routines: Labels, recipes, shopping lists, notes, calendars

Think of your environment as a “hidden curriculum” that teaches children what matters. A home filled with books sends a powerful message even before a single word is read aloud.

Read-Aloud Sessions and Their Impact

Reading aloud to children is perhaps the single most powerful activity for building literacy skills, and the research backs this up consistently. Even after children can read independently, continuing read-aloud sessions provides tremendous benefits.

Why read-alouds are so powerful:

- Exposure to vocabulary beyond children’s independent reading level

- Modeling fluent, expressive reading

- Shared enjoyment that builds positive associations with books

- Opportunities for discussion and comprehension development

- Cultural and emotional connections through stories

Best practices for effective read-alouds:

- Choose engaging, high-quality books slightly above the child’s independent reading level

- Preview the book and plan where you might pause for discussion

- Read with expression, using different voices for characters

- Pause to think aloud about confusing parts or interesting ideas

- Ask open-ended questions that promote thinking

- Connect the story to children’s lives and experiences

- Reread favorite books—repetition builds both skills and joy

Choosing Age-Appropriate Books

Not all books are created equal, and matching children with books at the right level and interest is crucial for developing both skills and motivation.

♦ Picture Books for Toddlers

For the youngest readers, picture books should feature:

- Clear, engaging illustrations that tell part of the story

- Repetitive or predictable text patterns

- Limited text per page

- Familiar topics and experiences

- Rhyme and rhythm that make language playful

Examples of classic choices: “The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” “Goodnight Moon,” “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?”

♦ Chapter Books for Early Readers

As children transition to independent reading, chapter books provide:

- Short chapters that provide natural stopping points

- Engaging plots with age-appropriate complexity

- Illustrations that support comprehension

- Vocabulary that stretches skills without overwhelming

- Characters and situations children can relate to

Popular transitional series: Magic Tree House, Junie B. Jones, Mercy Watson, Ivy and Bean

Proven Techniques to Improve Children’s Writing Skills

The Power of Daily Writing Practice

Just as musicians need daily practice and athletes need regular training, young writers need consistent opportunities to write. The key is making writing a regular, low-stakes part of daily life rather than only a formal school assignment.

Ways to incorporate daily writing:

- Morning journals: 5-10 minutes of free writing to start the day

- Thank you notes: Teaching gratitude and authentic writing purposes

- Story starters: Quick creative prompts for imaginative writing

- Lists: Shopping lists, wish lists, to-do lists

- Letters: Writing to pen pals, grandparents, or favorite authors

- Digital writing: Emails, texts, or blog posts (with supervision)

The goal is volume and frequency. Research shows that students who write frequently improve faster than those who only write occasionally, even if the frequent writing isn’t always formally assessed or graded.

Creative Writing Activities for Kids

Creativity is the spark that makes writing come alive. When children see writing as a tool for expressing their imaginations rather than just a school task, motivation soars.

Engaging creative writing activities:

- Story cubes or cards: Roll dice or draw cards with images to inspire stories

- Collaborative storytelling: Take turns adding sentences to create a group story

- Comic strip creation: Combine drawing and writing skills

- Personal narrative prompts: “My most embarrassing moment,” “The time I got lost”

- Alternative perspectives: Rewrite a familiar story from another character’s viewpoint

- Genre exploration: Try writing a mystery, adventure story, poem, or myth

- Writing from images: Use interesting photos as story inspiration

Key principle: Focus on ideas and expression first, mechanics second. Children who are anxious about spelling and punctuation often freeze up and write less. Encourage them to get their ideas down first, then revise later.

Teaching Grammar and Spelling Naturally

Nobody wants to go back to the days of endless grammar worksheets and weekly spelling tests that students forgot immediately after the test. Modern research supports teaching grammar and spelling in the context of actual reading and writing.

Effective approaches:

- Minilessons» Short, focused instruction on specific skills as they arise in student writing

- Mentor texts» Studying how published authors use grammar effectively

- Word study» Investigating spelling patterns and word families rather than memorizing lists

- Editing conferences» teaching proofreading skills during the revision process

- Interactive writing» Composing together and discussing conventions as they arise

When children understand that grammar and spelling help them communicate clearly rather than just being arbitrary rules, they’re more motivated to learn and apply these conventions.

Common Challenges in Children’s Literacy Development

Reading Difficulties and Dyslexia

Not all children learn to read at the same pace or in the same way. Some face significant challenges that require specialized support and intervention.

Signs of reading difficulties:

- Trouble recognizing letters and letter sounds beyond kindergarten

- Difficulty blending sounds or decoding simple words

- Reading significantly below grade level despite regular instruction

- Avoiding reading activities or showing anxiety about reading

- Strong listening comprehension but poor reading comprehension

- Family history of reading difficulties

Dyslexia, a specific learning disability affecting reading, occurs in approximately 5-10% of children. It’s neurobiological in origin and not related to intelligence. With appropriate specialized instruction (particularly structured literacy approaches), children with dyslexia can become successful readers.

What parents and educators should do:

- Seek evaluation from reading specialists or educational psychologists

- Implement evidence-based interventions like Orton-Gillingham or Wilson Reading

- Provide accommodations like audiobooks and extended time

- Focus on strengths while addressing challenges

- Maintain patience and positive expectations

Writing Struggles and How to Address Them

Many children who read well still struggle with writing. The physical act of handwriting, spelling, organizing ideas, and producing text simultaneously can be overwhelming.

Common writing challenges:

- Graphomotor difficulties: Physical trouble forming letters legibly

- Spelling struggles: Inconsistent or highly phonetic spelling that impedes fluency

- Organizational issues: Difficulty planning and structuring written compositions

- Motivation problems: Resistance to writing tasks or seeing writing as punishment

Helpful interventions:

- Break writing tasks into smaller steps (brainstorming, drafting, revising separately)

- Use graphic organizers to plan writing before drafting

- Teach keyboarding skills as an alternative to handwriting

- Allow oral composition before written production

- Provide sentence frames and writing templates as scaffolds

- Celebrate progress and effort, not just final products

Motivation and Engagement Issues

Perhaps the most challenging problem isn’t skill-based but motivation-based. Children who can read but choose not to miss out on the practice that builds fluency and the experiences that develop comprehension.

Why children lose reading motivation:

- Books that are too difficult or too easy

- Limited choice in what they read

- Only reading for assignments, never pleasure

- Lack of time for reading

- Competing entertainment options (screens, games)

- Not finding books that match their interests

Strategies to rebuild motivation:

- Choice: Let children select their own books within broad parameters

- Relevance: Connect reading to their interests (sports, animals, gaming, whatever they love)

- Social reading: Book clubs, buddy reading, family read-alouds

- Alternative formats: Graphic novels, magazines, audiobooks, ebooks

- Remove pressure: Allow leisure reading without reports or tests

- Model enthusiasm: Share your own reading life with children

The Role of Parents in Literacy Development

Building Daily Reading Routines

Consistency matters more than quantity. Even 15 minutes of daily reading together creates more benefit than occasional marathon sessions.

Creating sustainable reading routines:

- Bedtime reading: A classic approach that creates positive associations

- Morning reading: Starting the day with quiet reading time

- Weekend reading adventures: Library visits, bookstore browsing, reading in parks

- Mealtime conversations: Discussing what everyone is reading

- Reading challenges: Family goals like “read 100 books this year”

The key is making reading a predictable, protected part of daily life rather than something that happens only when there’s extra time.

Supporting Homework and Writing Projects

Parents walk a fine line between being supportive and doing too much. The goal is helping children develop independence while providing appropriate scaffolding.

Helpful parental support:

- Create a consistent homework space free from distractions

- Help break large projects into manageable steps

- Ask guiding questions rather than providing answers

- Proofread but don’t rewrite children’s work

- Communicate with teachers about challenges

- Celebrate effort and improvement, not just final grades

What to avoid:

- Completing assignments for children

- Over-correcting every error in writing

- Creating unrealistic expectations based on comparisons

- Making homework a battleground

- Ignoring genuine struggles that might require professional support

Modeling Reading Behavior

Children are natural imitators. They adopt the values and behaviors they observe in the adults around them, often more from what we do than what we say.

Ways to model literacy:

- Read your own books while children read theirs

- Share interesting things you’ve read

- Keep books, magazines, and newspapers visible in your home

- Write notes, lists, and messages

- Visit libraries and bookstores together

- Show children how you use reading in everyday life (recipes, directions, research)

When children see adults who read for pleasure, information, and purpose, they understand that literacy isn’t just a school requirement but a life skill and source of enjoyment.

The Teacher’s Impact on Reading and Writing Skills

Evidence-Based Instructional Methods

Teaching reading and writing effectively requires more than enthusiasm—it requires knowledge of evidence-based practices that research has proven effective.

Essential components of effective literacy instruction:

- Systematic phonics instruction: Explicit teaching of letter-sound relationships

- Phonemic awareness training: Direct instruction in manipulating sounds

- Fluency practice: Repeated reading and modeling of fluent reading

- Vocabulary instruction: Explicit teaching of word meanings across content areas

- Comprehension strategies: Teaching specific strategies like predicting, questioning, summarizing

- Writing workshop: Regular time for authentic writing with instruction and conferencing

| Instructional Component | Research Support | Implementation Time |

|---|---|---|

| Phonics Instruction | Very Strong | 25-30 min daily (K-2) |

| Fluency Practice | Strong | 15-20 min daily |

| Vocabulary Teaching | Very Strong | Integrated throughout day |

| Comprehension Strategies | Strong | 20-30 min daily |

| Writing Workshop | Moderate-Strong | 30-45 min daily |

Differentiated Instruction for Diverse Learners

No two children learn exactly the same way or at the same pace. Effective teachers recognize this and provide multiple pathways to literacy success.

Differentiation strategies:

- Flexible grouping: Changing groups based on specific skills rather than fixed “ability levels”

- Tiered assignments: Same learning goals with different levels of support or complexity

- Learning centers: Stations with varied activities addressing different skill levels

- Choice boards: Allowing students to select how they’ll demonstrate learning

- Scaffolded instruction: Gradually releasing responsibility as students gain competence

The goal isn’t to give some students easier work but to provide whatever support each student needs to access grade-level content and continue growing.

Technology and Digital Literacy for Modern Children

Educational Apps and E-Books

Technology is neither the enemy of literacy nor its savior—it’s simply another tool that can be used well or poorly. Quality educational apps and e-books can supplement traditional literacy instruction effectively.

Benefits of well-designed literacy apps:

- Immediate feedback on reading and spelling activities

- Adaptive difficulty that adjusts to individual learners

- Engaging multimedia that brings stories to life

- Accessibility features like text-to-speech for struggling readers

- Tracking progress over time

Recommended types of apps:

- Phonics and word-building games

- Interactive e-books with read-along features

- Writing and story creation tools

- Digital libraries with age-appropriate content

Warning signs of low-quality apps:

- Heavy advertising or in-app purchases

- No clear learning objectives

- Purely entertainment-focused without educational value

- Inappropriate content or lack of child safety features

Balancing Screen Time with Traditional Reading

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limiting recreational screen time for children while recognizing that not all screen time is equal. Educational reading on devices differs from passive video consumption.

Guidelines for healthy balance:

- Prioritize physical books for young children developing print awareness

- Allow e-books and educational reading apps as supplements

- Set device-free times and spaces (meals, bedrooms, first hour after school)

- Co-engage with children during screen time when possible

- Choose high-quality content over quantity of time

- Monitor what children read and encounter online

The research is clear: children still need hands-on experiences with physical books, face-to-face reading interactions with adults, and time away from screens for optimal development.

Bilingual Children and Literacy Development

Benefits of Biliteracy

Children who develop literacy skills in two languages enjoy cognitive, academic, and social advantages that extend well beyond just speaking multiple languages.

Advantages of biliteracy:

- Enhanced executive function and cognitive flexibility

- Greater metalinguistic awareness (understanding how language works)

- Improved problem-solving abilities

- Cultural connections and heritage language maintenance

- Career advantages in an increasingly global economy

- Transfer of literacy skills between languages

Research consistently shows that strong literacy in a home language supports rather than interferes with English literacy development. The skills, strategies, and concepts children learn about reading and writing transfer across languages.

Strategies for Supporting Multiple Languages

Parents and educators can support bilingual literacy development through intentional practices that honor both languages.

Effective approaches:

- Read books in both languages regularly

- Allow children to write in whichever language they choose initially

- Celebrate code-switching as sophisticated language use

- Connect literacy to cultural practices and family stories

- Find bilingual books or parallel texts in both languages

- Partner with bilingual educators or tutors when possible

What to avoid:

- Insisting children only speak English at home

- Treating the home language as inferior

- Expecting perfect simultaneous development in both languages

- Assuming that bilingualism causes reading difficulties

Assessment and Monitoring Progress

Recognizing Reading Level Benchmarks

Understanding typical reading development helps parents and educators recognize when children are progressing well and when additional support might be needed.

General reading level benchmarks:

- End of Kindergarten: Recognize most letters, read simple CVC words, show print awareness

- End of First Grade: Read simple sentences and books with 90%+ accuracy, use basic decoding

- End of Second Grade: Read fluently at level J-M (guided reading), show strong comprehension

- End of Third Grade: Read chapter books independently, summarize main ideas accurately

- End of Fourth Grade: Read across genres, make inferences, support ideas with evidence

- End of Fifth Grade: Analyze text structures, compare multiple texts, read critically

These are guidelines, not rigid requirements. Children develop at different rates, and some variation is normal. However, children significantly below these benchmarks may benefit from additional assessment and intervention.

Evaluating Writing Development

Writing assessment should focus on growth over time rather than comparing children to each other or arbitrary standards.

What to observe in children’s writing:

- Ideas: Are thoughts clear and interesting?

- Organization: Is there logical structure?

- Voice: Does the writer’s personality come through?

- Word choice: Is vocabulary varied and appropriate?

- Sentence fluency: Do sentences flow well?

- Conventions: Are spelling, grammar, and punctuation improving?

Assessment approaches:

- Portfolio assessment tracking work over time

- Rubrics that describe quality at different levels

- Self-assessment helping children evaluate their own work

- Conferencing to understand the writer’s process and intentions

The goal is always to identify next steps for growth, not to label children as “good” or “bad” writers.

Resources and Tools for Parents and Educators

Building strong literacy skills requires access to quality resources and support systems.

Essential resources:

For parents:

- Public libraries (free books, programs, librarian expertise)

- Reading apps: Epic!, Raz-Kids, Starfall

- Writing tools: Story Starters, Storybird, Book Creator

- Parent education: Reading Rockets (readingrockets.org)

- Support organizations: Understood.org for learning differences

For educators:

- Professional development: ILA (International Literacy Association)

- Lesson resources: Teachers Pay Teachers, ReadWriteThink

- Assessment tools: Running records, DIBELS, DRA

- Classroom libraries: Scholastic Book Fairs, DonorsChoose

- Research resources: What Works Clearinghouse

Books about teaching literacy:

- “The Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists” by Edward Fry

- “Writing Workshop: The Essential Guide” by Ralph Fletcher

- “The Book Whisperer” by Donalyn Miller

Conclusion

Children’s reading and writing development is a journey that begins at birth and continues throughout childhood and beyond. It’s a journey that requires patience, persistence, and partnership between children, parents, and educators. The path isn’t always smooth—there will be challenges, plateaus, and moments of frustration—but the destination is worth every effort.

Strong literacy skills are the foundation for academic success, professional opportunities, and lifelong learning. They’re also the keys to imagination, empathy, and self-expression. When we help children become confident readers and writers, we’re not just teaching school subjects—we’re opening doors to worlds of possibility.

Remember that every child is unique, with their own timeline, strengths, and challenges. The child who struggles with spelling might be a creative storyteller. The reluctant reader might transform when they discover books about their passion. Our job is to provide rich experiences, appropriate instruction, and unwavering support while honoring each child’s individual journey.

Whether you’re reading bedtime stories to a toddler, helping a second-grader sound out words, or discussing a novel with a middle schooler, you’re contributing to their literacy development in meaningful ways. Keep going. Keep reading together. Keep encouraging those early writing attempts. The impact you’re making extends far beyond today—it’s shaping who these children will become as learners, thinkers, and human beings.

FAQs About Children Reading and Writing

1. At what age should my child start reading?

Most children begin reading simple words between ages 5-7, but the foundation starts much earlier. Focus on building pre-reading skills from birth through activities like reading aloud, singing, rhyming games, and letter recognition. There’s significant variation in when children “crack the code” of reading—some read at 4, others at 7—and this variation doesn’t predict long-term reading ability. Early readers aren’t necessarily better readers by upper elementary school. What matters most is consistent exposure to language and books from an early age and appropriate instruction when formal reading begins.

2. How much should I help with my child’s writing homework?

Your role should be as a supportive coach, not a co-author. Help your child brainstorm ideas, talk through their thinking, and break the assignment into manageable steps. You can point out areas to revise (“Can you add more details here?”) but resist the urge to rewrite their sentences. It’s okay if their work isn’t perfect—mistakes are part of learning. If you find yourself doing significant portions of the work, the assignment may be too difficult, and you should communicate with the teacher. The goal is building independence, and children learn more from completing work themselves with support than from submitting parent-perfected projects.

3. Should I be concerned if my child reverses letters like b and d?

Letter reversals are extremely common in early writers and readers (typically ages 5-7) and usually resolve naturally with.

time and practice. The visual system is still developing, and distinguishing mirror images is neurologically challenging for young children. Concern is only warranted if reversals persist beyond age 8 or are accompanied by other significant reading struggles. Help your child by explicitly teaching visual cues (like “b has a belly” or using physical mnemonics), providing lots of writing practice, and being patient as their brain development catches up to the visual demands of literacy.

4. How can I help my child who hates reading?

Start by identifying the root cause. Is reading difficult (skill issue) or boring (motivation issue)? For skill issues, seek assessment and appropriate intervention. For motivation issues, focus on choice, relevance, and removing pressure. Let your child choose books about topics they’re passionate about, including graphic novels, magazines, or websites. Read together without requiring book reports or comprehension questions afterward. Connect reading to their interests (if they love basketball, find basketball biographies; if they love gaming, find books about game design). Sometimes the right book at the right time can transform a reluctant reader into an enthusiastic one. Be patient and keep modeling your own reading enjoyment.

5. Is it better to correct all spelling and grammar errors in my child’s writing?

No—this approach often backfires by making children anxious and inhibiting their willingness to write. Instead, focus on one or two teaching points at a time based on your child’s developmental level. For young writers, prioritize getting ideas down and celebrate their phonetic spelling as evidence of sound-symbol understanding. As children mature, teach them to revise and edit in separate steps after drafting. You might say, “Let’s make sure all your sentences start with capital letters,” focusing on one convention rather than marking everything in red. The goal is growth over time, not perfection in every piece. Writing frequently with selective feedback leads to more improvement than writing rarely with extensive corrections.